'A War Against Civilisation'

Annebella Pollen, The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift: Intellectual Barbarians

Donlon Books, 228pp, £35.00, ISBN 9780957609518

reviewed by Anna Neima

A dissonant, disquieting collection of over 100 images – many of them previously unseen – accompany art and design historian Annebella Pollen’s account of the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift: eye-catching, brightly coloured, Kandinsky-style designs; black and white photos of solitary, near-naked figures posed ritualistically out-of-doors; groups of young people dancing, hiking and camping in a heterogeneous range of costumes, some reminiscent of Robin Hood: Men in Tights and the modern craze for Live Action Role Play, others more ominously resembling the uniformed Hitler Youth or that other KKK, the Ku Klux Klan. They make a suitably bewildering introduction to a small, compelling and above all eclectic band of interwar idealists who, amid ‘ever-shifting purposes and practices’, had one clear ultimate goal – to create and lead a new world peace. With even their founder, John Hargrave, perplexed when called upon to set down an account of his organisation – ‘I hardly know what to call it: order, society, church, party, group?’ – Pollen sets herself a difficult task in chronicling its hitherto neglected story. It is a challenge she meets with elegance and flair.

The Kibbo Kift (‘proof of great strength’ in Cheshire dialect) was formed in 1920. It was, in the first instance, a reaction to the excessive militarism of Baden-Powell’s Boy Scouts, with whom Hargrave had been closely involved from a young age. More broadly, it was one of an array of what broadcaster Andrew Marr calls ‘the frantic, sometimes silly political searching of the twenties,’ which arose in response to the great psychic damage of the war and growing doubts about the sustainability of industrial modernism.

Hargrave was inspired by the historical theory that soft, sophisticated, settled civilisations will always, in the end, be overthrown by tough barbarian hordes coming in from the wilds. He conceived of the Kibbo Kift as just such a horde, ‘“Barbarian” stock’ who would lead corrupt and directionless modern society back to health. At the same time, his was to be a horde with a difference: it would be home-grown within society; and it would combine physical fitness, survival skills and primitive crafts with the most advanced thinking in art, science and philosophy – hence his chosen term ‘intellectual barbarians.’

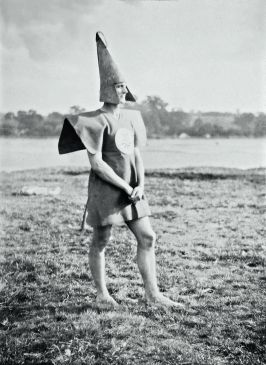

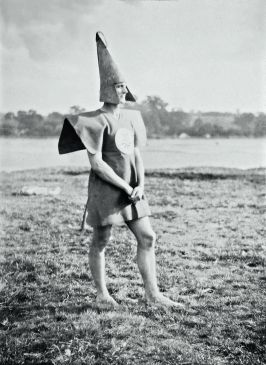

Body of Gleemen and Gleemaidens, Gleemote, 1929.

While never numbering more than a few hundred, Hargrave’s Kinsfolk managed to involve themselves in everything from camping and hiking to art, craft and design; myth-making and magic to economic theory and education. They were, as Hargrave wrote, ‘always experimenting with new things.’ Faced with such a range, Intellectual Barbarians is necessarily limited in its focus, skating over the group’s membership profile in favour of a close study of its spiritualism and aesthetics.

Though you’re left wondering who exactly the group appealed to, this is probably a wise choice: as Hargrave wrote, ‘the method of the Kibbo Kift is based upon a direct appeal to the senses by means of colour, shape, sound and movement, that is, by every form of symbolism.’ Within her chosen field, Pollen does an excellent job of knitting together a rich ephemera of handmade totems and banners, costumes and insignia, with detailed documentary archival research. Dividing the book into sections on Movement, Culture, Spirit and Resurrection, she unerringly follows the multiple skeins of the Kibbo Kift though the complex and colourful world of interwar British counterculture.

Pollen is particularly good at unpacking the Kibbo Kift’s extraordinary and often contradictory mixture of influences and characteristics: the revivalist and the hypermodern; the universalising and the exclusivity; the attractive and the deeply off-putting. The Kinsfolk wanted ‘away! Away! From men and towns’; they spoke out against ‘mechanical civilised slavery,’ urbanisation, modernisation; they banned gramophones from their camps. Yet they were determined that ‘Machines will be used when machine work is needed’ and hoped to establish motor and air squadrons to support their cause.

Their symbolism drew on a vast range of sources, from Ancient Egyptian, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon to contemporary ‘primitive’ groups, especially Native American and Pacific; but they borrowed, too, from the conspicuously modern. Futurist and cubist styles filtered into the group’s propaganda materials through Hargrave’s main job as an illustrator for an advertising agency and the official Kin photographer, Angus McBean, would later become famous for his surrealist style. The Kibbo Kift’s futurist utopia was, confusingly, both modernist and anti-modern.

Paul Jones (Old Mole) consecrating Old Sarum banner (Wessex Pilgrimage), 1929.

While treating the Kibbo Kift’s philosophy, ambitions and cultural productions with due seriousness, Pollen is also pleasingly deflationary about the results of its grandiose intention to ‘evolve a new race’ – not only for Britain but for the whole world. The organisation boasted an international membership, she writes, but scrutiny reveals that most locations only had a couple of members. It attracted the nominal support of such high profile writers, artists and scientists as Rabinandrath Tagore, Julian Huxley and HG Wells, yet few of them were actively involved.

One critical recruitment problem, which Pollen draws out nicely, was the impenetrability of Kibbo Kift’s speech and symbolism. A fairly typical example, intending to explain the reason for concealing certain information about a conclave within the organisation: ‘the Ndemno is a secret Order, regularly constituted after the manner of all other instituted rites, which by means of a peculiar system or symbolism advances its initiates in divers runes germane to the relationship existing between the Microcosm and the Macrocosm.’ Unsurprisingly, the Kibbo Kift seems often to have missed in its intention to guide the masses towards utopia. As one member put it, ‘We try to be too clever. To the common man our messages are the unrecognisable pictures of futurists.’ It is the penalty for such outlandish obscurantism, perhaps, that ‘serious’ historians have thus far paid little attention to the Kinsfolk’s cultural output. It is all the more fortunate that Pollen’s study now provides the key to their ‘enchanted land.’

Boys and men in the Touching of the Totems rite, Althing, 1925.

The other significant public relations problem was Hargrave’s exclusivist and dictatorial leadership. He set his Kinfolk above the rest of society, claiming that the ‘magico-political fraternities’ always held dominion over the ‘unthinking majority’. Although insisting his aims were sympathetic with other reform movements, he often delivered thundering broadsides condemning ‘the semi-demi-quavering New-Foods-and-theosophy freaks.’ Even within the group, he was autocratic and uncompromising – frequently quoting Samuel Butler’s view that bold assertion was more powerful than debate, he expected unfailing obedience. When it wasn’t given, members were sent a ‘Black Spot’ in the style of Treasure Island to indicate their expulsion. In 1924 there was a momentous ‘Rift in the Kift’, when a group of more democratically inclined members left to found a new group, The Woodcraft Folk. Almost a century on, this organisation still has 15,000 members. Its Kinsfolk-like emphasis on the value of creative expression and outdoor activity remain deeply resonant in the materialist, machine-orientated culture of today.

Ultimately, the only disappointment of Intellectual Barbarians is that Pollen does not extend her study into the 1930s, the decade when, as Andrew Marr writes, ‘the rambling stopped and the marching began.’ It was at this point that the Kibbo Kift’s penchant for spiritualism, ritual and ceremony morphed into a more conventional economic-political campaign group with a toned-down uniform and a new name, the Green Shirt Movement for Social Credit. Of particular pertinence now is its eponymous support for social credit: in simple terms, this was the theory that as production and consumption were out of balance, a National Dividend should be payable to every citizen to redress the disparity between wages and prices. It also demanded that financial control should be wrested from greedy bankers. One campaign ditty ran:

In a way, it’s a relief that, unlike other studies of 1930s organisations, the book’s secret subtitle is not ‘how this group was related/not related to Nazism.’ Yet there is still a sense that by skipping over that troubled decade, and then devoting an entire chapter to a recent revival of interest in the Kibbo Kift among fashion designers, artists and musicians, Pollen is deliberately avoiding an unsexy but intrinsic part of the group’s history. In this omission the book undersells itself, veering towards a cute, anthropological snapshot destined for the coffee table, rather than the full-blooded, pioneering history that it fundamentally is.

Both the Museum of London and the Whitechapel Gallery are staging Kibbo Kift exhibitions. A second book has been published alongside Pollen’s, Designing Utopia: John Hargrave and the Kibbo Kift by Cathy Ross and Oliver Bennett, which examines the two subsequent groups Hargrave went on to lead.

The Kibbo Kift (‘proof of great strength’ in Cheshire dialect) was formed in 1920. It was, in the first instance, a reaction to the excessive militarism of Baden-Powell’s Boy Scouts, with whom Hargrave had been closely involved from a young age. More broadly, it was one of an array of what broadcaster Andrew Marr calls ‘the frantic, sometimes silly political searching of the twenties,’ which arose in response to the great psychic damage of the war and growing doubts about the sustainability of industrial modernism.

Hargrave was inspired by the historical theory that soft, sophisticated, settled civilisations will always, in the end, be overthrown by tough barbarian hordes coming in from the wilds. He conceived of the Kibbo Kift as just such a horde, ‘“Barbarian” stock’ who would lead corrupt and directionless modern society back to health. At the same time, his was to be a horde with a difference: it would be home-grown within society; and it would combine physical fitness, survival skills and primitive crafts with the most advanced thinking in art, science and philosophy – hence his chosen term ‘intellectual barbarians.’

Body of Gleemen and Gleemaidens, Gleemote, 1929.

While never numbering more than a few hundred, Hargrave’s Kinsfolk managed to involve themselves in everything from camping and hiking to art, craft and design; myth-making and magic to economic theory and education. They were, as Hargrave wrote, ‘always experimenting with new things.’ Faced with such a range, Intellectual Barbarians is necessarily limited in its focus, skating over the group’s membership profile in favour of a close study of its spiritualism and aesthetics.

Though you’re left wondering who exactly the group appealed to, this is probably a wise choice: as Hargrave wrote, ‘the method of the Kibbo Kift is based upon a direct appeal to the senses by means of colour, shape, sound and movement, that is, by every form of symbolism.’ Within her chosen field, Pollen does an excellent job of knitting together a rich ephemera of handmade totems and banners, costumes and insignia, with detailed documentary archival research. Dividing the book into sections on Movement, Culture, Spirit and Resurrection, she unerringly follows the multiple skeins of the Kibbo Kift though the complex and colourful world of interwar British counterculture.

Pollen is particularly good at unpacking the Kibbo Kift’s extraordinary and often contradictory mixture of influences and characteristics: the revivalist and the hypermodern; the universalising and the exclusivity; the attractive and the deeply off-putting. The Kinsfolk wanted ‘away! Away! From men and towns’; they spoke out against ‘mechanical civilised slavery,’ urbanisation, modernisation; they banned gramophones from their camps. Yet they were determined that ‘Machines will be used when machine work is needed’ and hoped to establish motor and air squadrons to support their cause.

Their symbolism drew on a vast range of sources, from Ancient Egyptian, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon to contemporary ‘primitive’ groups, especially Native American and Pacific; but they borrowed, too, from the conspicuously modern. Futurist and cubist styles filtered into the group’s propaganda materials through Hargrave’s main job as an illustrator for an advertising agency and the official Kin photographer, Angus McBean, would later become famous for his surrealist style. The Kibbo Kift’s futurist utopia was, confusingly, both modernist and anti-modern.

Paul Jones (Old Mole) consecrating Old Sarum banner (Wessex Pilgrimage), 1929.

While treating the Kibbo Kift’s philosophy, ambitions and cultural productions with due seriousness, Pollen is also pleasingly deflationary about the results of its grandiose intention to ‘evolve a new race’ – not only for Britain but for the whole world. The organisation boasted an international membership, she writes, but scrutiny reveals that most locations only had a couple of members. It attracted the nominal support of such high profile writers, artists and scientists as Rabinandrath Tagore, Julian Huxley and HG Wells, yet few of them were actively involved.

One critical recruitment problem, which Pollen draws out nicely, was the impenetrability of Kibbo Kift’s speech and symbolism. A fairly typical example, intending to explain the reason for concealing certain information about a conclave within the organisation: ‘the Ndemno is a secret Order, regularly constituted after the manner of all other instituted rites, which by means of a peculiar system or symbolism advances its initiates in divers runes germane to the relationship existing between the Microcosm and the Macrocosm.’ Unsurprisingly, the Kibbo Kift seems often to have missed in its intention to guide the masses towards utopia. As one member put it, ‘We try to be too clever. To the common man our messages are the unrecognisable pictures of futurists.’ It is the penalty for such outlandish obscurantism, perhaps, that ‘serious’ historians have thus far paid little attention to the Kinsfolk’s cultural output. It is all the more fortunate that Pollen’s study now provides the key to their ‘enchanted land.’

Boys and men in the Touching of the Totems rite, Althing, 1925.

The other significant public relations problem was Hargrave’s exclusivist and dictatorial leadership. He set his Kinfolk above the rest of society, claiming that the ‘magico-political fraternities’ always held dominion over the ‘unthinking majority’. Although insisting his aims were sympathetic with other reform movements, he often delivered thundering broadsides condemning ‘the semi-demi-quavering New-Foods-and-theosophy freaks.’ Even within the group, he was autocratic and uncompromising – frequently quoting Samuel Butler’s view that bold assertion was more powerful than debate, he expected unfailing obedience. When it wasn’t given, members were sent a ‘Black Spot’ in the style of Treasure Island to indicate their expulsion. In 1924 there was a momentous ‘Rift in the Kift’, when a group of more democratically inclined members left to found a new group, The Woodcraft Folk. Almost a century on, this organisation still has 15,000 members. Its Kinsfolk-like emphasis on the value of creative expression and outdoor activity remain deeply resonant in the materialist, machine-orientated culture of today.

Ultimately, the only disappointment of Intellectual Barbarians is that Pollen does not extend her study into the 1930s, the decade when, as Andrew Marr writes, ‘the rambling stopped and the marching began.’ It was at this point that the Kibbo Kift’s penchant for spiritualism, ritual and ceremony morphed into a more conventional economic-political campaign group with a toned-down uniform and a new name, the Green Shirt Movement for Social Credit. Of particular pertinence now is its eponymous support for social credit: in simple terms, this was the theory that as production and consumption were out of balance, a National Dividend should be payable to every citizen to redress the disparity between wages and prices. It also demanded that financial control should be wrested from greedy bankers. One campaign ditty ran:

‘Are we to starve with Plenty all around us? Are we to die, because of Money Law? In Battle cry the Money Power has ground us Into the Dust and Death of Bankers War’

In a way, it’s a relief that, unlike other studies of 1930s organisations, the book’s secret subtitle is not ‘how this group was related/not related to Nazism.’ Yet there is still a sense that by skipping over that troubled decade, and then devoting an entire chapter to a recent revival of interest in the Kibbo Kift among fashion designers, artists and musicians, Pollen is deliberately avoiding an unsexy but intrinsic part of the group’s history. In this omission the book undersells itself, veering towards a cute, anthropological snapshot destined for the coffee table, rather than the full-blooded, pioneering history that it fundamentally is.

Both the Museum of London and the Whitechapel Gallery are staging Kibbo Kift exhibitions. A second book has been published alongside Pollen’s, Designing Utopia: John Hargrave and the Kibbo Kift by Cathy Ross and Oliver Bennett, which examines the two subsequent groups Hargrave went on to lead.