A Raging Peace

by Marc Farrant

Is it possible to imagine Kraftwerk – the electronic crusaders at the vanguard of Krautrock – without Germany? David Stubbs’ remarkable book dances on the pivot of this construction, demonstrating without lofty pretension or academicism, the compatibility of the utterly abstract and the doggedly objective. If music is the condition to which all art aspires, this no doubt derives from its immediacy, its freedom from linguistic or pictorial signification. This makes writing about music an impossible task – akin, in the words of Frank Zappa, to ‘dancing about architecture.’ Krautrock’s musical expression, in the late 1960s and 1970s, no doubt emerges because of this impossible potential inherent to music’s break from the world; that is, the potential to make a new one.

The music and people David Stubbs gathers under the term ‘Krautrock’ mark precisely this definitive question of post-war German life: how to start afresh? Their musical innovations similarly bear testament to the inextricability of geography, of nations and wars, whilst also proffering a radical interrogation of these tyrannical logics. Krautrock is portrayed as blurring the stable boundaries upon which arbitrary identities are forged: ‘Man–Technik–Natur.’ No Führers. Transformation and renewal. Stasis and kinesis. Combinations best expressed, in music journalist Julian Cope’s phrase, as ‘a raging peace’. Krautrock was a many-headed Hydra, whose gestation exemplifies precisely the contingency of foundations that pervades and energises its most vertiginous moments.

*

‘Utopia’ means ‘nowhere’ in Greek, and there is nowhere that is more like nowhere than West Germany. A bricolage of facades mask a cracked history, wherein furious activity still fastens all hope to the imminent future promised by an industrious present. Berlin’s concrete timeless newness disguises a relatively recent rise in hipster fortune, one that follows a more myriad and radical shift of cultural paradigm that arose in West Germany after the war. Kraftwerk’s 1978 album The Man-Machine bears the inscription ‘Product of West Germany’, a geographically accurate but more specifically conceptual demarcation. As Stubbs outlines,

The circumstances which gave rise and shape to it were to do with the condition of that temporary, federal state – prosperous, ashamed, liberal in many respects but clinging to conservative illusions … in conflict with its own youth, fragmented by national disunity, riven by traumas, disconnected from its past, having possibly sold both its soul and its identity for the dubious bounty of American materialism.

Adding to the mix the failed policy of denazification, and the proliferation of AltNazis in bureaucratic, administrative and government roles across the state, conditions were ripe for the utter dejection, alienation and radical transformation of the German youth. Yet Krautrock’s multiplicity fails to encapsulate in a single word, for instance, both ‘the ambient extremes of Ash Ra Tempel and the heavy industrial collage of Faust. The faux-bourgeois placidity of Kraftwerk and the angry, messy agitation of Amon Düül.’ These aesthetic differences are also manifest in various philosophical, societal and economic differences. Munich’s Amon Düül (and Amon Düül 2) are distinctly different in both sound and appearance to Kraftwerk, whose relatively prosperous origins act as a springboard for the ironic assault on precisely that element of German society. Emerging from the commune scene that similarly housed Baader Meinhof, Amon Düül reject both the Anglo and the German, drawing on exotic Eastern music while rejecting its Western transmutation (Yes and Genesis) in the ‘elaborate lands of make-believe.’ As John Weinzierl recalls; ‘I wanted to make “space’ music” but realised it was impossible because you can only draw on your terrestrial time. People talk about Pink Floyd. You can make “spacey” music, yes, but space music, no.’ Variations were also manifest in hair, clothing and drug choice (early Düsseldorf-based Kraftwerk look remarkably different from the later, finished, machined article).

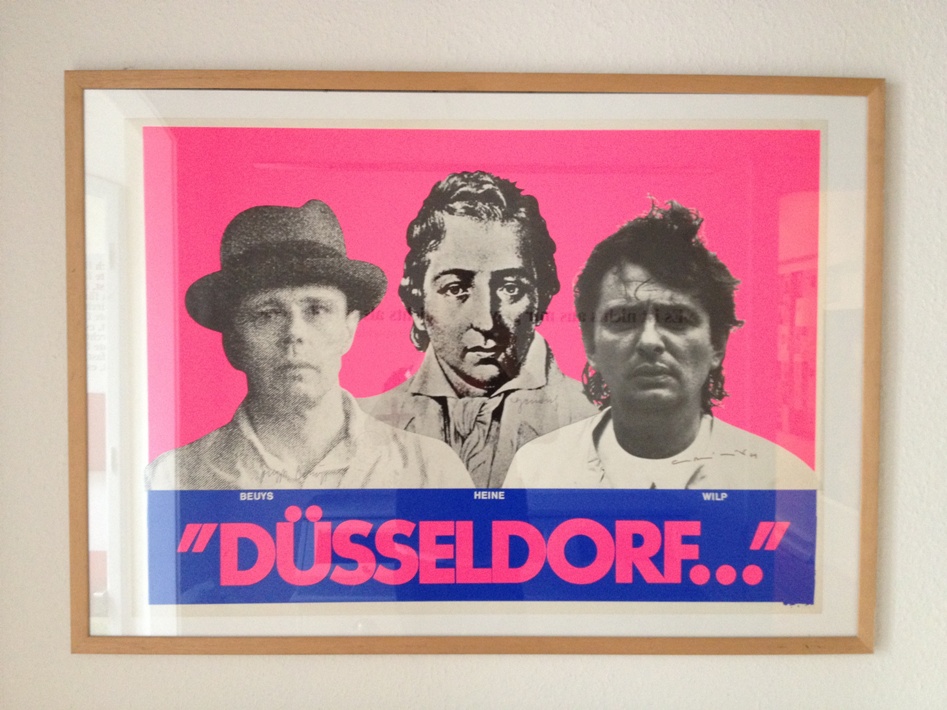

Joseph Beuys, Heinrich Heine, Charles Wilp.

Today, however, in Kraftwerk’s hometown of Düsseldorf one is more likely to hear other musical locals, Die Toten Hosen, and their anthemic ‘Tage Wie Diese’ (or ‘Strom’, the chorus of which is played on the rare occurrence of local Football club, Fortuna, scoring a goal) than the minutiae of Kraftwerk’s reverberating electro-locomotion, ‘Trans-Europe Express’. The crowds that populated the famous Ratingerhof, celebrated by Krautrock-inspired British post-punk group Wire, as epitomising an openness that was difficult to find in Britain at the time (‘there was a culture of non-American rock music to which we felt really connected.’) were never in the majority. As Simple Mind’s Jim Kerr explains: ‘Germans don’t get it. I’ll discuss the German influences, Faust [Hamburg] and so on, with them, and they don’t know what I’m talking about.’ The tenacity and indelibility of Anglo-American Rock still holds sway, even in Berlin; a phallic, white, repetitive force of unspecific teenage angst, a force initially liberating for the generation of Krautrockers growing up in the 1960s, before becoming the stifling embodiment of American cultural colonisation. Indeed, the attraction and then rejection of Anglo-American music (from Free Jazz to the Beatles), often only accessible in and around Allied army bases, helps elucidate Krautrock’s relation to its homeland, from which would ultimately spring both natural and cultural forces of inspiration in the face of pugnacious derisions and inevitable stereotyping.

*

Rheinische culture remains a relatively little-known source of regional identity, especially when compared to the Rococo flatulence of the lederhosen-sporting, sausage-munching, beer-guzzling tourist traps of Bavaria. As Cologne resident Max Ernst wrote with obvious glee: ‘Here, the principal currents of Europe meet: early Mediterranean influences, Western rationalism, East tendencies towards Occultism, Nordic mythology, the Prussian categorical imperative, the ideals of the French revolution and much besides.’ Today, Cologne is the gay capital of Germany, a liberal magnet for artists and young people (historically exemplified by Karl Marx, who would return to Cologne after the failed revolutions of 1848, and found the radical newspaper Neue Rheinische Zeitung). More widely, the state of North-Rhine Westphalia (NRW) – the country’s most populous – encompasses Bonn, former Capital of the West German Republic (remarkably still home to six Federal ministries), Düsseldorf, business centre and arguably the locus of Krautrock, the entirety of the Ruhrgebeit and its almost inconceivably vast industrial landscape (including the mined chasms of former coal pits, large enough to fit the entirety of Washington DC underground), and one of the most impressive regionally-owned art collections in the world.

This regional strength draws on a number of external and still present facets, including a Dutch-like atmosphere of hospitality (and drinking), a Hanseatic prosperity (despite Cologne’s location hundreds of Kilometres inland) and a French proximity (Napoleon was very fond of Düsseldorf, despite only a fleeting visit, and French traces are still observable in the food across the region). Similarly, the region’s Roman origins, manifest on the west bank of the Rhine as a series of trading outposts – most notably Cologne (from the imperial designation, Colonia) – testify to a historic strength and geographic independence. Cologne was the largest city north of the alps at a point when Munich, Hamburg and Berlin simply did not exist. Cologne, however, ceded its status as NRW capital to Düsseldorf after the war. (Düsseldorf is, as Cologne-folk are ready to explain, on the wrong side of the river, the barbarian side. An old Kölsch joke goes: ‘What’s the best thing about Düsseldorf?’ To which the answer runs, ‘The autobahn to Cologne.’) The latter’s rise in fortunes, however, explains its undoubted status as epicentre of Krautrock, producing not only the movement’s most successful offspring but also, along with Kraftwerk, its defining aesthetic — its status as art.

Zeche Zollverein. Centre of the Ruhr Industrial Heritage Trail. Essen.

Rising from the ashes of the decimated Third Reich (literally: the western cities were the first to feel the force of the allied 1,000 bomber raids), Düsseldorf (seized with relative ease from the capitulating Wehrmacht) radiates the image of a free-market anti-historicism that would have appalled Hitler; a timelessness markedly different from the eternal, millennial Reich, revealing the inherent finitude of any given concept of eternity. Vertical glass and concrete towers and structures now dominate over older industrial relics, physical manifestations of the Wirtshaftswunder; temples to international business that far exceed the towns of the neighbouring Ruhrgebeit (‘thanks not least to architects like [Florian] Schneider’s father’). Despite this, Düsseldorf and Cologne both maintain an industrial feel, even if Duisberg, Essen and Dortmund form a far greater industrial scar on the banks of the Ruhr, just to the north (one of Germany’s most ethnically diverse areas, historically home to thousands of Gastarbeiters). Despite this continued prosperity (a prosperity that may well be coming to an end), the overall effect of the juxtaposition across the region – tradition and innovation, dense urban landscapes and voluminous rural heartland – conjures the status of flux that still animates Germany’s physical and psychological landscapes. Similarly, despite the rhetoric of ‘recent history’, the Second World War is now undeniably somewhat abstract, definitely of the past, yet its ingrained image often fails to capture its actual ramifications: the French were still extracting coal from the Saarland until 1981, and Germany was still technically obligated to continue reparations until re-unification in 1990 (although, earlier this year, Greece reopened the debate.)

Indeed, Stubbs formulates just such a juxtaposition of old and new in his Bildungsroman of Krautrock, drawing on a German tradition of innovation exemplified by the link between Germany’s belated yet advanced industrialisation, and its enduring emphasis on the development of skilled craftsmen, with technical colleges now replacing Germany’s unique medieval Guild system – a factor often cited as being central to Germany’s continuing economic and societal strength. The perfect metaphor for this opposition, however, is undoubtedly the gleaming German autobahn, scything through the dense forested hinterland. The first stretch of autobahn was between Cologne and Bonn, its Weimar origins long predating the network’s later Nazi associations. The experience of the road becomes foundational to Krautrock as precisely that link between technology, history and nature, manifest in a specifically German way (for example, Germany’s most congested section of autobahn – the Bundesautobahn 40, alongside the Ruhr between Essen and Dortmund – lies above the Westphalian Hellweg, the most significant ancient trading road in medieval Germany, stretching from Duisberg to Paderborn, and then on to the Elbe river). As Stubbs explains, ‘there’s no comparison for this in the UK. Hit the road in England and its dull sprawl of conurbations, and within barely an hour you’ll have hit a Derby, a Watford, or a Doncaster.’ In Germany, ‘as with America, the sheer space impacts on the music, and the journeys undertaken across it affect its sense of narrative.’

'Ganz Anders, Doch Gleich' [wholly different, exactly the same]. Sterntor, Bonn.

Autobahn would be Kraftwerk’s 1974 breakthrough album, and also Krautrock’s breakthrough album. Playing on a sense of Heimat (a longing for home that pervaded popular culture, the music of Schlager, and the visual corollary of the Heimatfilm, both exhibiting a ‘Proustian waft of Euro-dreadfulness’) in the earlier album Ralf & Florian, Kraftwerk present both an ironic and deeply felt engagement that filters through into Autobahn:

tinkling pianos and multi-tracked flute evoking slow mists moving over beautiful, stagnant waters ... an ahistorical, melancholy, pastorial idyll, nostalgia, perhaps, for a time and place that never was.

This is achieved through Kraftwerk’s pioneering use of electronics, notably the vocoder. On the title track 'Autobahn' this innovation is evident as a ‘brilliant evocative sonic depiction of a car journey, using a paintbox of chromium-plated melodies and sweeping synthstrokes’, acquired sounds from a series of real motorway journeys, reworked into the music via a newly acquired sequencer. This timbre of ‘exquisite monotony’ is signposted in the song’s opening lyric, ‘fahr’n fahr’n fahr’n’ (travel, travel, travel), a subtle pun on the Beach Boys’ ‘Fun, Fun, Fun’.

Autobahn disposes of the entire roster of Anglo-American Rock clichés which cling to the metaphoric power of the road; it is antithetical to Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Guitars, babes, authenticity, thunder.’ Might Kraftwerk be accused of provoking a wilful naïveté in this supposed celebration of, and blind faith in, technological, modernist progress; of Hitlerlian and authoritarian town planning, ‘carved monstrously across the verdant landscape’? As Stubbs answers:

For Kraftwerk, celebration of the autobahn was not mere bourgeois cheerleading but a return to prewar Bauhaus principles in which art and technology were melded together in a single purpose; another branch of the broader project of twentieth-century art to connect art with life...’Our roots were in the culture that was stopped by Hitler’, said [Ralf] Hutter, ‘the school of Bauhaus, of German expressionism’.

Kraftwerk’s origins in Entartete Kunst (Hitler’s designation of modernism as ‘Degenerate Art’) also derive, in part, from Düsseldorf. Home to the famous Kunstakademie, whose illustrious roll-call of students and teachers include Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter and Joseph Beuys. Beuys' own unique project to collapse the gap between art and life, partly via harnessing the power of self-dramatisation, would be an important touchstone in the Düsseldorf arts scene, essential ‘in the nurturing of groups like Kraftwerk and Neu!. And it was as a response to the killing of Benno Ohnesorg that he founded the Deutsche Studentpartei (German Student Party).’ Beuys was directly concerned with the ‘German trauma’, and art was seen as integral to forming the quilting interventions needed to patch-over the fabric of social life. Kraftwerk’s own identification with the notion of Gesamtkunstwerk (a total work of art, encompassing multiple mediums, fields, meanings etc.) is no doubt influenced by this formative proximity (and is now the centrepiece of the band’s multimedia live performances). In Cologne, meanwhile, the influence of revolutionary post-war composer, Karlheinz Stockhausen, would have an immediate and pronounced impact of Krautrock’s unfolding tale. Stockhausen’s electric compositions of the 1950s, on early manipulative analogue equipment, greatly affected the musical formation of Can’s Irmin Schmidt and Holger Czukay, and their own komische productions. (Can would move away from Stockhausen’s maxim of no repetition, seizing on an informative paradox: ‘that real liberty in music arose from the strict and rigid imposition of order, regularity.')

User-generated content. Post-war citizens' submissions for the design of a new German flag. Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn.

Similarly, the advertising industry, which still has its headquarters in Düsseldorf, was swiftly incorporated by Klaus Dinger of Neu! (formerly of Kraftwerk, and pioneer of the distinctive Dingerbeat: the 4/4 motorik) in titles, logo and sleeve art; a direct attempt to engage popular consciousness. Charles Paul Wilp was perhaps the most famous of Düsseldorf’s legions of Ad-men, whose photography book Dazzledorf: ‘Suburb of the World’ (referencing, in the subtitle, JG Ballard’s remarks on the city) features Beuys, amongst other artists. Wilp worked on a number of famous campaigns (including for Volkswagen) and as an image consultant for major politicians, like Willy Brandt. Advertising not only captures the aesthetic of techno-capitalist modernity, it also estranges ‘the consumer’ from specificity and locality, gesturing towards a utopian future of potential, immanent plenitude. Düsseldorf’s early department stores also embody precisely this logic, art-deco and expressionist prototypes of the shopping malls that would replace the 19th-century arcades of Paris worldwide, and still lend the Carlstadt area a distinctly Chicago-like feel. Incidentally, Chicago was the American city that opened the gates to Kraftwerk’s international invasion. Not only would the band draw on the technological advancements of their age to project their own, different versions of a possible sonic future, this initial distancing from one’s own oppressive, provincial domesticity (whether via Anglo-American rock or consumer goods) was an artistic imperative. As filmmaker Chris Petit recalls, Düsseldorf projected exactly this sense of future immanence: ‘When I visited them [Kraftwerk] in Düsseldorf in 1978, both group and town seemed to belong to the future more than anything in England, but who could have guessed what a global force Kraftwerk would become. As for Düsseldorf, the writer J.G. Ballard has noted that the whole of Europe is a Düsseldorf suburb now. We’re all part of the same conurbation and drive German cars: UK plc has turned into a giant Mercedes/BMW concession.’

Haus Der Technik. Essen.

If the future was imperative, however, the trick was not to fall into the amnesiac state of one’s Spiesser (square) parents; to elevate materials and functions to art, rather than reduce art to commodity. This would fly in the face of a generation who had worked so hard – rebuilding a desolate land, including moving 500,000,000 cubic yards of rubble, and establishing the economic miracle – to bequeath to their languid children the perpetual peace offered by the voluntary amnesia of white goods. The endemic disavowal of Germany’s near history by the parents of the Krautrock generation is tracked by Stubb’s as a definitive feature not only of post-war Germany, but of the radicalism of the break Krautrock inaugurated: ‘a poll in 1968 revealed that while only a tiny number of people desired restoration of a Hitler-style Reich, fifty per cent of the West German population believed that Naziism was a “good idea badly executed.”’ (A higher percentage than when the same question had been put in the late 1940s). Similarly, the first large-scale psychological study of the denial of post-war West Germans, Alexander and Margarete Mitscherlich’s The Inability to Mourn (1975),‘noted the astonishing lack of guilt and shame they felt.’ As the historian Tony Judt summarises: ‘If ever there was a generation whose rebellion really was grounded in a rejection of everything their parents represented – everything: national pride, Nazism, money, the West, peace, stability, law, democracy – it was “Hitler’s Children”, the West German radicals of the sixties.’ Rather than sheer arrogance, Stubbs attributes the inability to atone or even acknowledge – by Germany’s wartime generation – to a ‘profound lack of self-esteem; a feeling that any sense of national identity had been wiped out, along with any sense of sustaining myth or memory.’

*

The list of Krautrock descendants is astonishing, and forms the subject of Stubbs’ conclusion. As the Wire’s Colin Newman recalls; ‘It’s not that we were self-consciously anti-American, it’s that we were British. If you were from Salford, why would you want to sing about Route 66? But at the same time, singing about the Arndale Centre didn’t quite do it… So in 1978, I started a love affair with continental Europe.’ By 1978, however, Krautrock was already winding down, its groups disbanding, its aesthetics tiring, and to a certain extent, its mission complete. Electronic music was popular music. Disco had arrived – in Munich, contemporaneously, at the hands of Giorgio Moroder and his Moog-based synthesiser wizardry – and there was no going back. Similarly, the explosion of Punk’s profane zeal would do its bit to undermine the centrality of the White Male rock star, and further Krautrock’s ‘cult of impersonality’. Along with Bowie, Brian Eno, Talking Heads and early electronic pioneers – The Normal, Cabaret Voltaire – Krautrock would hugely influence post-punk, with the Fall, Sonic Youth, Joy Division, Pavement and others all citing the inheritance. Although succeeding German groups, the Neue Deutsche Welle – including Düsseldorf-based D.A.F. and Der Plan – would differ drastically in tone from Krautrock, the common ground is evident: ‘the same early take-up of available electronic technology, the same preoccupation with form, with tearing down and beginning anew, the same driving imperative to innovate. Groups like Neubaten, D.A.F. and Der Plan represent not a negation of Krautrock but, rather, a compact postscript.’ As John Doran, co-founder of the Quietus, acknowledges: ‘it seems to me that “Autobahn” represents the birth of modern music.’

If Krautrock’s practitioners are, in Shelley’s phrase, the ‘unacknowledged legislators’ of our musical world, then the music’s contemporary revival in Berlin is, to a certain extent, inevitable. As the one place in Germany where Germanness can still be exotic, and this sense of self-fascination no doubt explains the migratory magnetism of the place, where Krautrock is an integral part of the orientalising logic that draws thousands of wealthy, travelling bohemians, hipsters and postgraduate students, no doubt participating in the same delights as Bowie: ‘drinking coffee and eating Turkish food, exploring the city’s decadent underbelly.’ Yet, for Krautrock’s ‘hipness’, as Stubbs says, it is still poorly understood, which perhaps explains the concurrent, perhaps ironic, conflation with the GDR nostalgia fad known as Ostalgie.

Transformation and renewal. Bunkerkirche St. Sakrament, Düsseldorf. Former air-raid bunker, now church.

Future Days unveils a more radical, musical impulse, throwing a truly revealing light on this often tarnished musical sub-species. Stubbs writes with a deftly honed lyricism, sometimes ironic, often humorous, always entertainingly illuminating, with the love of an enthusiast but without the dryness of the Hobbyist. If Krautrock emerged from the same milieu, from the same socio-political conjuncture, as Baader Meinhof, its politics evince none of the latter’s destructive and wanton tendencies. Instead, Krautrock critiqued, via the ironic fetishisation of the prevailing tradition of today (the material, technological world), which is not quite today but the ‘tradition of today’, the endless today of planned obsolescence, of wilful absent-mindedness, of forgetting-as-imperative; the ‘con’ of the contemporary. Nevertheless, American commercialism never gained quite the foothold in Germany as elsewhere — an unabashedly commodified ‘counterculture’ is conspicuous by its absence. Alternatively, perhaps there wasn’t quite the same market for such an entity, as Faust’s Jean-Hervé Péron suggests: ‘the art didn’t need to be that clear – we didn’t need to care of this situation. In the States, maybe someone like Dylan was needed, but in Germany and France we had a whole generation of young people writing pamphlets, books, essays, forming demos.’

Krautrock’s Gedankenexperiment (thought experiment) offers a window into a radical alternative German experience, a window that it is hard to imagine any other book could frame better: an experience of regionalism without parochialism, of autonomy without tyranny, of equality without homogeneity. The light of the west that drew so many from the east (exacerbating a dire situation immediately after the war’s end, where 66% of the houses in Cologne were destroyed, and Düsseldorf was 93% uninhabitable) still persists with an inextinguishable glow. However, Krautrock does more than manufacture from the ruins of this industrial soundscape. It also points critically and obliquely to the effervescent seeming-permanence of this socio-political spectacle, proposing at least one simple question: when the lights are on, why not dance ‘a raging peace’?

Future Days: Krautrock and the Building of Modern Germany by David Stubbs is published by Faber.