Goodbye, Chauvinism: A First World War Primer

by James Heartfield

My great uncle Davey Poole ended up with those British troops under TE Lawrence fighting alongside the Arabs in revolt against the Ottoman Turks (then allies of Germany). Davey told us that the British would pay the Arabs a shilling for every Turk’s head they brought them. Tom Barry was in the same army, fighting in Mesopotamia ‘a battle ground for the two contending Imperialistic armies of Britain and Turkey’. He was used to hearing news about enemies from all over the world, but having signed up in Cork still surprised to see the special communique ‘Rebellion in Dublin’ – he was the enemy! Back home he led the West Cork Flying Column which pinned down 12,500 British troops in the war of independence (Barry’s Flying Column evaded detection by the cunning manoeuvre of following his pursuers).

Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisholm were motorcycle enthusiasts – and in love, in a way – who left Bournemouth to set up their own hospital in Belgium, who were known as the Angels of Pervyse. As a prank they put visiting big-wigs on one end of a see-saw, which at its height was open to the German guns, drawing a great fusillade. (Di Atkinson, who wrote their story, is raising funds for a statue to commemorate them, with the backing of the Belgian parliament).

Ludwig Wittgenstein was in an artillery regiment attached to the Austrian Seventh Army, where, in between calculating missile trajectories, he wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: ‘The men, with few exceptions, hate me because I am a volunteer.’ Another volunteer in the Austrian Army was the young Adolf Hitler, who was invalided out, temporarily blinded by mustard gas, who would later think that the military had been ‘stabbed in the back’ when the politicians surrendered.

These are just a few of the 67 million men and women who fought in the First World War, that broke out one hundred years ago. They were arranged in the armies of the Allied (Russia, British Empire, France, Italy, America and others) and the Central powers (Germany, Austria, Ottoman and Bulgaria). Ten million soldiers died, and 20 million were wounded.

The way we see the First World War has been argued about in the newspapers. Last July the Oxford history professor Richard J. Evans pilloried Education Secretary for peddling a nationalistic version of British history and preparing a propaganda fest around the anniversary of 1914. Gove replied with a plaintive article in the Daily Mail that asked why we cannot have our British heroes, and (drawing on the arguments of theology professor Nigel Biggar) why do ‘Guardian writing left wingers’ like Evans mock nationalism? Gove argued that the Blackadder version promoted in schools had more recently been called into question by historians. Historian and Labour frontbencher Tristram Hunt joined Evans in telling the precocious schoolboy Gove that he needed a lesson in history.

As history wars go, this so far has been a storm in a tea-cup. The belligerents of this battle are pugnacious. All Education Secretaries are hated, but Michael Gove has drawn the hostility aimed at the Con-Dem coalition like a lightning rod. Richard Evans is something of a scrapper, too. He was lead witness in the libel trial against the far right historian David Irving, took on the might of the revisionist German historians, the Historikerstreit, who wanted to normalise their nation’s history, and he has fought some wild skirmishes in the review pages, against Thomas Snyder and most recently AN Wilson. Whether the row over the First World War was started by Gove or Evans is a moot point, but one thing is sure: there will be no trenchant right-wing campaign to make us feel patriotic about the First World War. Michael Gove and Nigel Biggar might want that (and in his own way, Richard Evans might, too) – but the truth is that there is no appetite for a militaristic or chauvinistic account of the First World War.

How different it was in 1919. At the peace conference Germany’s war guilt was established as a condition of the peace under clause 231, and punitive measures imposed (reparations, and the surrender of territory). The German delegates were made to wait outside while the victors discussed terms, and only called in at the end to sign.

Article 231: The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.

The ink was barely dry on the document though when the first doubts about the guilt clause and the punitive peace were raised. Both John Maynard Keynes and Edward Hallet Carr were at the conference, for the treasury and the Times respectively. Keynes’ Economic Consequences of the Peace showed that reparations would arrest recovery after the war, while Carr’s two books, International Relations Since the Peace Treaties and The Twenty Years’ Crisis 1919-1939, argued that the punitive peace backed Germany into a corner.

Carr and Keynes recoiled at the atavistic national chauvinism that demanded an attribution of guilt. To them the dispassionate, scientific approach was better. Even during the war the Union of Democratic Control – set up by pacifists Norman Angell and E D Morel and supported by Bloomsbury-ites like GE Moore and Leonard Woolf – pushed for a more rational and less emotional response to the conflict. As Frank Furedi explains in a fine meditation on the still unresolved meaning of the conflict, First World War – Still no End in Sight (Bloomsbury, 2014), many intellectuals were repulsed by national chauvinism because it was popular. Of course in 1914 most of the intelligentsia were thrilled by war fever – but they quickly came to fear the disorder that war offered, and also the call upon the masses war propaganda made. For them mobilised public opinion was a great current of irrationality that endangered liberal institutions.

Woodrow Wilson’s deal-brokering at Versailles, with the 14-point charter for the League of Nations – national self-determination to the fore - was backed up with sharp criticism of the old European imperialisms. Though the colonised of Africa and Asia were not freed, their rule was renamed as a League of Nations ‘mandate’, indicating that it was temporary. In September 1934, US Senator Gerald Nye opened a hearing into the munitions industry in the First World War – the ‘merchants of death’ – saying: ‘when the Senate investigation is over, we shall see that war and preparation for war is not a matter of national honour and national defence, but a matter of profit for the few.’

The growing elite scepticism over the justice of the Great War, was easily matched by the popular disaffection. All Socialist Parties in the early century were committed to opposing war – though it was a promise more honoured in the breach than the observance. When the Socialists in Parliament got carried away with war fever and voted for it, they wrecked their parties, and were challenged by yet more radical opponents of war, notably VI Lenin’s Communist International. It was Lenin who popularised the claim that capitalism was inherently war-like, and that its imperialist turn was not accidental, but in its nature.

The possibility of war is given in the division of the world into different states – and as some say, inherent in human history (Buzan and Little, International Systems in World History). In his The Origins of the First World War (Routledge, 2013), James Joll pointed to the arms race that mutual distrust brought as an important cause, where ‘no government had in fact been deterred from arming by the arms programmes of their rivals, but rather had increased the pace of their own armament production.’ It was thought that conflict was contained by the ‘balance of power’. To offset their mutual distrust nations would enter into alliances, so that no one power predominated in Europe. The Oxford historian Hew Strachan showed how the Alliance system that had moderated conflict in the 19th century had become entrenched, so that Alliances turned from being convenient counters to a power imbalance, to becoming an overwhelming set of mutual obligations and promises that ended up increasing the tension.

It was a multi-ethnic team of Bosnian rebels – the Bosnian Serbs Gavrilo Princip and Nedeljko Čabrinović , and the Bosnian Muslim Muhamed Mehmedbašić - who started the chain reaction when they assassinated the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand. The Austrians issued the July Ultimatum demanding the Serb government take draconian measures against Serbian nationalists, and then invaded. Russia was committed to defend Serbia, and massed troops ready to attack Austria. Germany was pledged to defend Austria and massed troops to attack Russia. France was committed to defend Russia, and massed troops against Germany. German troops crossed the Belgian border to meet the French. Britain declared war against Germany for the invasion of Belgium.

The chain of events leading to war, and the obligations of diplomatic and military alliances, though, do not wholly explain the drive to war. War was embraced as a positive goal. The military elite planned for war with enthusiasm. And, as Arno Meyer explains, the drive to military conflict helped elites that were challenged by mass movements of the working class. Reckless brinkmanship was, in the words of Arno Mayer, 'intimately tied in with those social, economic, and political strata that were battling either to maintain the domestic status quo or to steer an outright reactionary military course.' Social conflicts within European nations were relocated onto the international stage. That was why the outbreak of war was so widely celebrated, particularly by elites. Horatio Bottomley’s patriotic paper, John Bull lauded

The Dawn of England’s Glory. The Day has Come. Now for the Golden Eventide … It is not necessary to be a soldier but it is necessary to be a MAN.

The troubled logician Wittgenstein’s motives for going to war were more ambiguous: ‘Perhaps the nearness of death will bring light into life.’

War enthusiasm was not limited to the officer classes. ‘From the beginning of the War until the end,’ wrote Sidney Webb, ‘the Labour Party stuck at nothing in its determination to help the Government win the war.’ Many ordinary soldiers signed up with enthusiasm. ‘I went to the war for no other reason than that I wanted to see what the war was like, to get a gun, to see new countries and feel like a grown man,’ remembered Tom Barry, who later became leader of the Cork IRA . Harold Eagles lied about his age to join up. The educationalist Martin Stephen, who completed a doctorate on the war poets, interviewed hundreds of veterans in the 1970s and found that many were proud of what they had done, and often unhappy with the patronising account of them as ‘cannon fodder’.

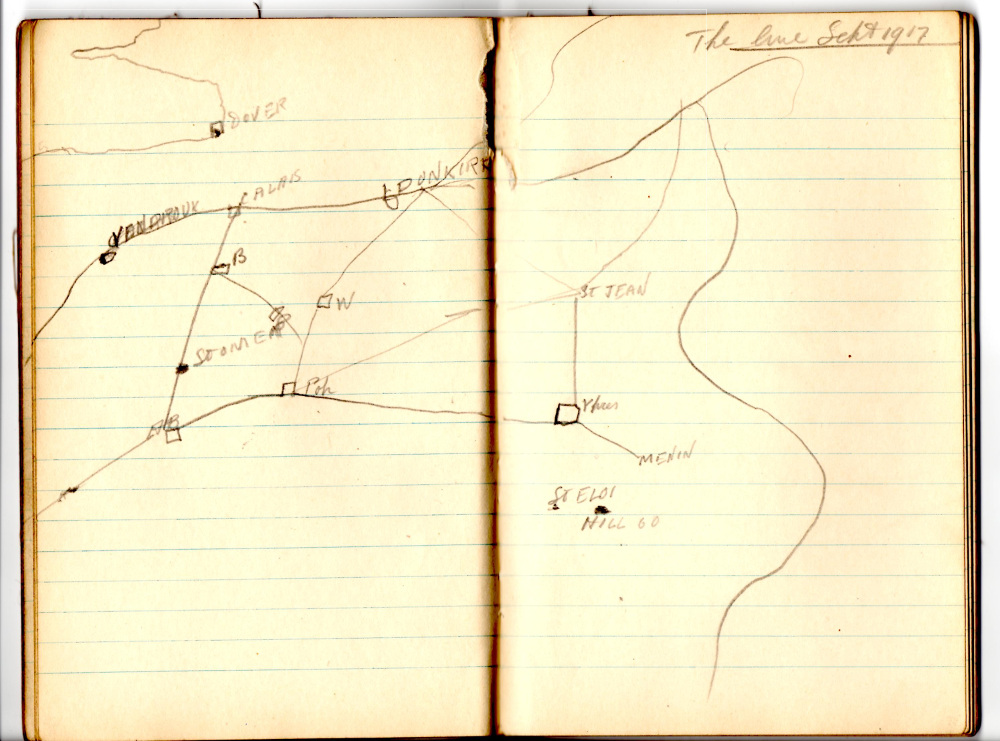

From the Allied Headquarters Major Charteris wrote in the winter of 1914 that ‘General Rice our senior sapper has made the most original forecast of all! He predicts that neither we nor the Germans will be able to break through a strongly defended and entrenched and that gradually the line will extend from the sea to Switzerland, and the war will end in stalemate.’ So it did. ‘It was impossible to dig deeper than eighteen inches without finding water, and along whole stretches of the line garrisons had to do their stint waist high’ according to Alan Clark. Worse: ‘the wounded who collapsed into the slime would often drown, unnoticed in the heat of some local engagement, and lie concealed for days until their bodies, porous from decomposition, would rise once again to the surface’. Harold Eagles was buried in a pit of mud and the bodies of his own comrades, and would never talk about it afterwards. Mairi Chisholm wrote in her diary:

No one can understand ... unless one has seen the rows of dead men laid out. One sees men with their jaws blown off, arms and legs mutilated.

The hope that war would overcome the problems of a stagnant society at home only ended up with a yet more appalling stalemate on the Western Front. It was a Moloch, swallowing up fresh recruits. The best-known voices of war-weariness – thanks to hundreds of earnest schoolteachers – are those of the intellectuals, the war-time poets, like Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon – though none of the veterans that Martin Stephen interviewed had a copy of Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’. You can see something of the Tommies’ view of the war in the pages of the trenches newspaper, the BEF Times: they are not exactly disloyal, but casually scathing about the pretensions of the officer class, military propaganda and life under orders. The Czech volunteer Jaroslav Hašek parodied the absurdity of unthinking and irrational orders in his mammoth account The Good Soldier Schwejk(1923).

In time war weariness gave way to outright disobedience and even mutiny. The Christmas armistice was real, and, more troubling for the General Headquarters, soldiers once having stopped fighting were not keen to take up arms again on Boxing Day, for weeks on many parts of the line. The mutiny in the brutal training grounds of the Bull Ring, at Étaples, that feature in the BBC Drama that so exercised Michael Gove, the Monocled Mutineer, was real, too (though it is not clear that Percy Toplis was there). More serious of course was the outright revolution in Russia that pulled her out of the war (despite the best efforts of Kerensky and, surprisingly, the anarchist Prince Kropotkin, to fight on against Germany). Finally the November Revolution in Germany overthrew the Kaiser’s government and drew a close to the war.

Despite winning the war – or at least not losing it – Britain was beset by militant challenges. Throughout 1916 the Clyde Workers Committee, based on the munitions and engineering workers that were driven on by war preparation, challenged not the war itself, but their working conditions and pay. Engineers struck in 1917, and then again at the end of the war, after the so-called Khaki election in 1918, mounting a serious challenge to the social order. In Ireland, then still ruled from Westminster, Sinn Fein won the overwhelming majority of seats in the election, and created its own rebel Dáil Éireann and raising an Irish Republican Army to fight the British. In 1920 Joseph Hawes of the Connaught Rangers, an Irish regiment in the British Army in India, ‘put the point that we were doing in India what the British forces were doing in Ireland’, sparking a mutiny.

The history of the First World War that the Education Secretary Michael Gove, his opposite member Tristram Hunt, Richard Evans and others have argued about is of course contested. Gove is right to say that the pacifist interpretation of the First World War got stronger further from the war. One of those who elaborated that interpretation was the very right-wing Conservative MP Alan Clark, in his book The Donkeys (1961), which was damning about the General Staff. Clark was called out over the quote that the British troops were ‘Lions, led by Donkeys’, and joked that he had made it up; he did misattribute it, but it was said in the German headquarters according to a 1920 memoir by Evelyn Blücher, an expatriate English aristocrat.

Clark’s researches were used by Joan Littlewood for her caustic musical Oh! What a Lovely War! of 1963. The 1960s were a time of anti-war feeling, and other wars, like the Crimean, were also mocked. But in painting a less than flattering picture of the British war effort then, Littlewood and Clark were already drawing on the disaffection of the earlier period. (The best contemporary anti-war account is Pat Mills and Joe Colquhoon's multi-volume comic book Charley's War.) Dismay about the Great War, and cynicism about its outcome, were endemic in the 1930s. Indeed to make the case for the Allied effort in the Second World War, policymakers found it necessary to distance themselves from that earlier war, which they characterised as narrow, chauvinistic, and inspired by war profiteers. That much was an attempt to make the case for the Second World War - as a war of humanitarian purpose, and noble cause - more persuasive.

Those arguing over the First World War will find out soon enough that there is neither the opportunity nor the danger that there will be an upsurge of nationalistic identification with the British war effort. The depleting forces of popular militarism are clear for all to see.